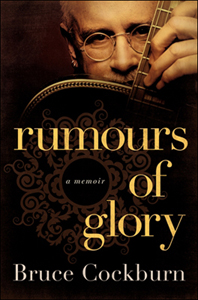

26 January 2015 - At four p.m., Canadian singer-songwriter legend Bruce Cockburn strides into the hotel lobby in his signature black Doc Martens and shakes my hand warmly. At age 70, he is slighter than he appears in his old music videos. He’s here to talk with me about his spiritual memoir Rumours of Glory. The book narrates his journey of faith and activism, explaining the stories behind his songs and his choices.

We take the elevator to a business lounge, a cozy gold-tinted room outfitted with two computers and nearly-trendy transparent plastic chairs. Despite his big name and stack of music awards, the setting seems luxurious, since Cockburn’s international activism has been far from first-class; he’s been to war zones in Mozambique, Guatemala, Honduras, and Iraq, where set up camp amongst refugees and in decrepit hostels.

“Writing the book was like writing a song,” Cockburn says as we each take a seat in our respective plastic chairs. “I feel like a bloodhound sniffing out a trail and sensing that there’s something there to discover.”

And in essence, Rumours of Glory is just that: its pages mirror Cockburn’s songwriting. Part personal narrative, part social commentary, part didactic, the memoir allows the audience to learn by posing questions.

When I read the book, I tell him, I was so fascinated by the history of the issues and places he unearths; the logical next step was to explore them for myself.

As I say this, he chuckles. “I’m certainly not the only one who’s mentioned those things, but the invitation is out there,” Cockburn says. Wryly, he smirks. “I guess it’s proof it’s the same guy writing.”

Originally, Cockburn says he was going to arrange the book in vignettes, with various scenes that add up to a whole. It was his co-writer Greg King’s idea to arrange it chronologically; Cockburn says King urged him to put in a lot more of the political background that drives the book. When HarperCollins asked for a spiritual memoir, Cockburn says he hadn’t considered pairing it with so much of the political tensions that have driven his travels. But it makes sense that the two twine together, just as they do in his songs.

In high school, Cockburn discovered his grandmother’s guitar in his attic. He was then inspired to become a musician, and was eventually initiated into the Ottawa music scene in the mid-1960s. Cockburn played with a number of outfits, even opening for the Jimi Hendrix Experience in 1968, until he decided to pursue a solo career.

In the 1980s he started to pursue international activism; his songwriting became infused with deep concerns for human rights, the environment, and faith. During this time he spent a good deal of his shows explaining his songs to the audience. “Specifically, it was the song ‘If I Had a Rocket Launcher,’” he interjects as I mention the time period. “When I first came up with the song I felt it could be so easily misconstrued; I didn’t want people to take it wrong and think I was telling them to go down and kill Guatemalan soldiers. I wanted to make sure people got it right.”

I ask him whether he still finds himself needing to explain those stories. “Not very often, and not very much,” he says. “I think I’ve said enough in print about it, and now there’s the definitive version in the book,” he says. “So I’ll tell people to read that!”

One of the strongest themes in Rumours of Glory is his dismay at social elites who ignore alarming truths about systemic violence. He uses the example of The Washington Wives’ self-appointed censorship that prevented Cockburn’s songs about poverty and injustice from being aired. All because of a single profanity in “Call It Democracy.” Ironically, this line accused social elites for being calloused towards the marginalized.

Though he weaves stories from all areas of life into both his book and his song lyrics, Cockburn has been adept at keeping his personal life out of the spotlight of the press. “The memoir ends before my second daughter was born,” he says. “And that’s a start of a whole new story, which would have taken another 200 pages and taken us past the publisher’s deadline!”

He pauses. “If anything, it’s a set-up for volume two, just in case I ever forget how bad it was writing one book, or, more to the point, if my wife ever forgets; she thought the book was ruining my life.”

The memoir closes with a recognizably spiritual afterword on the responsibility of all people to nurture a relationship with the divine, and to practice healing of our world. From the language Cockburn uses, some readers may come away with a sense that he has undermined the singularity of the Christian faith by preaching universalism.

When I ask him about it, he is pleased to elaborate. “I’ve flirted with so many tribes over the years. A lot of people’s lives have converged with mine for a time,” he says. “You can get picky about other religions — take Shinto, for example — and call them all superstition. Or you can honour the profound things that are expressed through that belief system. And you can walk away thinking, ‘I could learn something from these people,’” says Cockburn.

“I don’t claim to be an authority on anything, and I really don’t think anyone should be claiming to be an authority on anything.”

Cockburn says he is grieved by the deep scars that have been inflicted upon humanity when people dig their heels into exclusive claims to truth. We witness it, he says, in the inability of “a significant portion of the right-wing Christian community” to see that they are of the same persuasion as those they call radical in the Middle East.

“Above all, you can’t go around killing people because they don’t agree with you. We need to pull the plank out of our own eye and our own psyche before we try to fix someone else’s wiring,” he says.

“When I look around at the mystical traditions, filled with people who have been reticent to share their knowledge, nowadays they are just throwing it out there. Maybe it’s an impulse from God encouraging us to get together, to love each other, to love the planet, and see miracles happen,” says Cockburn.

He speaks with the experience of age, where little is shocking, and yet he does so without much cynicism. I see the hope instilled in him by good gifts that cause him to wonder: his daughter, his friends, and his faith.

I can’t help but think that the world needs a few more Bruce Cockburns, keeping us wide-eyed enough to stop destroying the world, one another, and ourselves. Around us is a world filled with violence because we refuse to really see and hear people who are different.

Because, like Cockburn, we need to be lovers in a dangerous time.

~ from Converge Magazine.