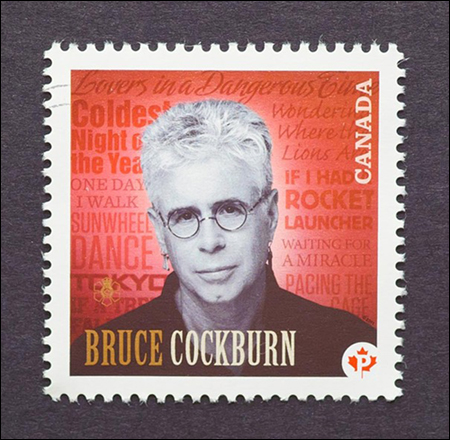

[Canada's postal service issued a 2011 Bruce Cockburn stamp in an edition of more than 7.5 million.]

[Canada's postal service issued a 2011 Bruce Cockburn stamp in an edition of more than 7.5 million.]

14 February 2018 - The traditional lullabies that parents sing to their children have been known to include disturbing images: babies in cradles falling from trees, children who fear dying in their sleep, that kind of thing. But none of them, as far as we know, have involved assault weapons.

Until recently, that is, when singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn was contacted by a fellow Canadian who'd made international headlines last October.

A revered singer-songwriter, Cockburn is best known here in the States for his unlikely mid-'80s hit, "If I had a Rocket Launcher." According to Rumours of Glory, his 2014 autobiography, Cockburn had been visiting Guatemalan refugee camps, and after returning to a hotel room, was in tears as he wrote the song. While many who've heard the song may not be familiar with its backstory, there was no overlooking its infamous last line: "If I had a rocket launcher / Some son-of-a-bitch would die."

"I was forwarded an email from Joshua Boyle, who I don't know at all, but he's the guy who was rescued from captivity in Afghanistan just recently with his wife and three kids," says Cockburn of the unusual interaction. "He's a Canadian guy who is married to an American woman, and they were captives of the Taliban for five years. And during that time, he sang 'Rocket Launcher' to his kids as a lullaby. They were just toddlers, so they wouldn't get what the song's about at all. But you could get what he was feeling, though — or, I can surmise at least, you know?"

Over the course of his career, Cockburn has won 12 Junos awards — the Canadian equivalent to the Grammy. Last year, he was inducted into the Canadian Hall of Fame, an honor that coincided with the September release of his 33rd album, Bone On Bone.

While it's been largely underplayed in his music, Cockburn turned to Christianity early in his career, and, apart from a period in which he became fed up with the intolerance of the evangelical right, he still identifies that way today. A rock musician whose music has incorporated elements of folk, jazz and world music, he's been hailed as one of contemporary music's most gifted guitarists, yet sings and plays in an understated way that complements lyrics that can be both poetic and polemical.

Bruce Cockburn

@ Boulder Theater

2032 14th Street

Boulder, CO

Fri., Feb. 16, 8 p.m. (sold out)

"On the coastline, where the trees shine, in the unexpected rain / There's the carcass of a tanker, in the centre of a stain," he sings on the new album's poignant "False River," while other songs show a wry sense of humor that surfaces from time to time: "Café Society, a sip of community / Café society, misery loves company / Hey, it's a way, to start the day."

Taken as a whole, the album is musically engaging and, in its own way, spiritually uplifting, something that will come as no surprise for his legion of fans. It also showcases his exceptional skills as a guitarist, as well as an occasionally more gritty side to his vocal style.

Cockburn's upcoming Boulder show, which will feature his full band, comes well into a more than 50-date tour, no small feat for a musician who last year turned 72. In the following interview, he talks about making the new album, how "Rocket Launcher" relates to Trump's America, and thinking of himself as a singer-songwriter until proven otherwise.

Indy: Reading your book, I think I learned more about certain aspects of the American experience than from my high school history classes...

Bruce Cockburn: That's not all that surprising. [Laughs.]

Indy: That's basically my question: American curriculums leave out topics like John Foster Dulles and the United Fruit Company. Are you still surprised, ever, by what we don't know in the States about our own history?

No, not really. But I don't think the States is worse than most countries in that respect. I think that every country, and every society, has an image of itself that it wants to perpetuate. And I don't even think it's that wrong, as long as the information is out there for people that want to find it. If you start suppressing information in a vigorous way, then it becomes something else.

I think Americans look inward more than they look outwards, in that people think, "Oh, I was going to go on a trip but I don't have to go anywhere outside of the United States to get anything I want by way of a holiday." And it's kind of true — if you're looking for a beach or if you're looking for a ski experience — I mean, it's a country that has a lot of stuff to offer.

Indy: There's a line in Harper Lee's Go Set a Watchman where she's writes about the small Alabama town the book is set in. "If you did not want much," she writes, "it was plenty." Would you say that summarizes part of the American thought process?

Yeah, although it's changed over the years. I remember how my family would all get in the car and drive from Ottawa down to Daytona Beach in Florida for Easter holidays. It took three days back then to do that drive, and I remember stopping at a gas station in Georgia, and the guy pumping the gas, a middle-aged man, said, "Where are you all from?" And my dad said, "Well, we're Canadians, we're from Canada." "Canada? What state is that in?" So I mean, that's in the '50s, right? It's changed, I don't think you'd get that now. Now people are too aware of hockey and the Blue Jays. And the NAFTAs.

Indy: How do you think the response to "If I Had a Rocket Launcher" would be different if you released it today? I mean, that song was in heavy rotation on a lot of American stations, but the line "some son-of-a-bitch would die" is a little extreme. I could see that being quietly banned now.

“Hearing 2,000 people sing ‘some son-of-a-bitch would die’ is a very disturbing thing.”

I could see that, but I wouldn't assume it automatically either, because I thought it would be banned back then. Like when it was suggested that it be sent out to radio stations as a single, or as the lead track from the album, or whatever it was, I said, "Nobody is going to play that, like, this is ridiculous." And yet we know what happened.

But the thing is, I think actually, if anything, it might even be more popular now, because everybody's mad. I mean everybody is overtly angry now. And back then, it wasn't that so many people cared about Guatemala — I mean, there were those who did — but I think a lot of people liked it because it was an expression of outrage, of a sense of what they would feel as their own rage at life.

Indy: Yeah, as long as you didn't listen to the words.

Well right, but people don't, and I know intelligent people who have had conversations where they'll go, "Oh you mean you're supposed to listen to the lyrics?" It's like, "Yeah!"

Indy: But you can't sing along as easily on the verses.

Yeah, exactly. Although I did play it at a festival in England, in a circus tent with 2,000 people in it, and they all sang along with it. And hearing 2,000 people sing "some son-of-a-bitch would die" is a very disturbing thing. It wasn't meant to be a sing-along, but there they were singing. And these were 2,000 Christians, as well.

Indy: A few days ago, I saw the news that Energy Transfer Partners — the same company building the pipeline through Standing Rock — has been given a final go-ahead, after two years, to run a pipeline through Louisiana's Cajun country.

Yeah, yeah. It's a disaster.

Indy: Were there specific circumstances that inspired you to write the song "False River"?

There were, but they're not what the song describes. It's a composite of images having to do with that kind of stuff, but the trigger for the song was a request from a woman named Yvonne Blomer. She's the poet laureate of Victoria, British Colombia, and she put a book together of environmental-related poetry as part of the movement specifically against the pipeline that they want to put right close to Vancouver there, across the Rockies. There's another one further north that's also very contentious and probably will, sooner or later, go through. I mean, eventually they usually win. But there's a lot of opposition to put both of these in. So she asked if I would contribute a poem. And I don't really write poems, but I thought, well, maybe I can do this?

Indy: All you have to do is leave out the music and that makes it a poem.

Well, that sometimes is true, and I think in that case, it was. Most of the times if I were writing for the page, it would look a little different, because you do a lot of things for rhythmic reasons you wouldn't necessarily do for the visual on a page. But, in my mind, when I was writing that song, I had a kind of hip-hop rhythm, which informed the pacing of the lyrics. So it was written as a poem for that collection, but it was obvious to me, even before I finished it, that I was probably going to try to make a song out of it. And so I did so.

Indy: Speaking of poetry, can you tell me a bit about "3 Al Purdys." How you ended up writing a song about a homeless guy going around shouting his poetry.

Well this was another one — it's weird — this album has two anomalies in it that were both the result of requests to write songs for other projects. In this case, there were people making a documentary film about [Canadian poet] Al Purdy, and they asked if I would contribute a song to the film. And I had not written anything for years, because I was too busy working on my book and that soaked up all the creative juices, and there was nothing left for songwriting. So when the book was done, I'm sitting there kind of going, "Well, am I a songwriter now or not?" It had been four years since I wrote a song and that's the longest it's ever been since I started.

I mean I was kind of figuring I would still keep thinking of myself as a songwriter until proven otherwise. But I wondered about that, and I was kind of sitting and waiting for an idea to come. So this invitation to contribute a song came. I didn't know very much about Al Purdy myself, so I went out and I bought his collected works, and he's a knockout. I mean he's just a great poet, and quintessentially Canadian in a way, but he also transcends that.

And right away I thought of the phrase "I'll give you three Al Purdys for a $20 bill" coming out of the mouth of somebody. And then I thought, who would that come out of the mouth of? And I pictured this guy with his hair blowing in the wind and a scruffy beard. And he's kind of an older guy, and he's out there on the street ranting out Purdy's poetry for money. So the spoken-word parts of the song are quotations from Al Purdy, and the rest of it I wrote in the voice of that guy.

Indy: A number of your vocals on the new album feel bluesier than usual, even though the music is still kind of all over the place. How do you view this album musically, especially in light of the 30 or so that came before it?

I don't spend much time thinking about that kind of comparison, but it's kind of where I'm at now — whatever that means. The lyrics invite the music for the most part. There are other decision-making factors, but a set of lyrics will tell me whether they want to be performed on an electric guitar or an acoustic guitar, or whether they want to have a certain kind of rhythm. So a song like "Café Society" just wanted to be bluesy.

Indy: So after this tour, what will your next recording project be?

There are no plans to record right away — this album hasn't run its course and I'm still feeling good about singing these songs — so that's it for the time being. But two things that we've talked about doing as long-range, somewhere-down-the-road projects are another instrumental album. We did one called Speechless a few years ago that was a mixture of new pieces and previously recorded ones, and we might do a volume two of that, which I would quite like to do. And I'd also, if I don't die first, like to eventually do an album of other people's songs. But I don't know.

Indy: Any artists in particular?

No, lots of different people. People that I admired. Dylan would be there, and Elvis would be there, and whatever other things I might dredge up from the depths.

~from www.csindy.com - Colorado Springs.