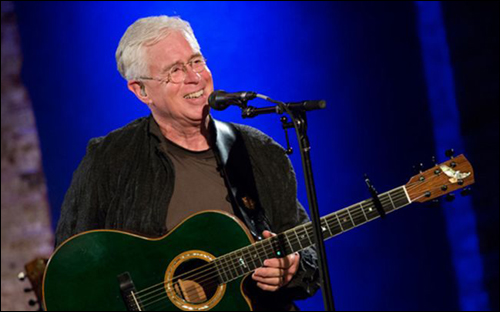

9 December 2014 - When many artists visit New York, they stay at downtown hotels like the Mondrian or the Bowery. Bruce Cockburn stays nearby at the Soho Holiday Inn. In town to launch his new memoir, Rumours of Glory, with a concert and book signing, the iconoclastic singer-songwriter arrives in the lobby wearing a modest outfit of black pants, black combat boots and a long black coat.

"This is not your standard rock & roll memoir," Cockburn writes in the book's preface. "You won't find me snorting coke with the young Elton John or shooting smack with Keith Richards." So what do you find? "I suppose it's about growing up," he says, ordering a glass of wine in the lobby bar. "It didn't require a decision to expose myself in the book, especially because the mandate was to write what the publisher was calling a spiritual memoir."

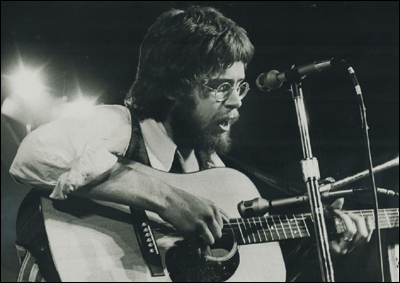

Rumours opens with the 69-year-old's awkward but comfortable childhood and covers his formative years in the Sixties folk-rock scenes in Ottawa and Toronto. In early bands, he opened for Cream, the Lovin' Spoonful and Jimi Hendrix. "I asked an audience recently if they wanted me to read about the origin of 'If I Had Rocket Launcher' or meeting Jimi Hendrix," he says between sips. "Everybody yelled out 'Hendrix!'"

During an 18-month stint at Berklee College of Music, Cockburn was more interested in writing poetry than transcribing scales, but he soon developed his signature style – "a combination of country blues fingerpicking and poorly absorbed jazz training" – by using his right thumb to carry the rhythm and his fingers to play melody. "Mississippi John Hurt and the old blues guys were the musicians I admired when I was young," he says.

The music Cockburn made during this period can be heard on Rumours of Glory's accompanying box set, a 117-song collection sequenced to parallel the book to allow the reader to hear the evolution it describes. One major turning point: the 1976 album In the Falling Dark, which marks the beginning of Cockburn's turn away from traditional Christianity and toward the all-inclusive mysticism he professes now.

"It was apparent fairly quickly that I didn't belong in that camp," he says of his time in the church. "I couldn't be that literal about things. I couldn't accept myself as a fundamentalist, and that meant moving in a more mystical direction." Yet even in his explicitly Christian phase, he aimed never to be an ideologue or proselytizer. "Nobody has to do anything," he says. "God offers freedom, as far as I understand it."

This evolution has profoundly affected not just generations of fans but some of the most important songwriters of our time. Graham Nash calls Cockburn "the consummate troubadour, a musical hero to many who are trying to make the world a better place," and Jackson Brown tells Rolling Stone that "few songwriters have been able to express as coherently the impulse for justice and the quest for moral equilibrium." To Bonnie Raitt, he is "a huge inspiration."

In recent years, Cockburn's spiritual odyssey has come to include even Jungian-based dream therapy. "That's what gave me the image of Christ as a collective animus," he says. "But is he more of a collective animus figure than Buddha? I don't think so." The dream therapy has also led to an interest in neuroscience and the nature of consciousness. "The idea of God as the boundless, as an undefinable and in a certain way unapproachable being except by proxy, has a lot of validity," Cockburn says. "That means sometimes he's going to seem like a hallucination or a motivator of things we don't really want to see. There's a juicy element of chaos about that, and that's where I tip over into 'I don't have a clue.'"

He continues: "Why are we different from raccoons? We believe we're special, historically and by nature, but who knows how raccoons see things? In some universe, parallel to this one, raccoons may be running the place. That's a nice thought. None of us knows shit from Shinola, and the people who claim they do know are grasping at straws – or worse."

Accordingly, a good deal of this self-described loner's later music brims with ecstatic emotion: "When I play music and my mind goes away from my ego and from my day-to-day concerns, I become more open to the Divine. I'd love to be in an ecstatic place all the time. It would feel a lot better than how I feel most of the time – that's the point of singing hymns in church. The snake handlers get that. Ecstasy is good, but I don't want to be bitten by a rattlesnake to get ecstatic."

Beyond belief systems (or lack thereof), the Rumours of Glory book and box set offer a call to life, embracing the mysteries of existence and the search for love and beauty, wherever one finds it. Part of that, of course, is a fine meal now and then, even if it's eaten in the bar aat a Holiday Inn. Following the wine, Cockburn orders a burger: "Just right."

~from Rolling Stone - Bruce Cockburn - Rumours of Glory.