NEWS ARCHIVE:

FolkWax Is Sittin' In With Bruce Cockburn

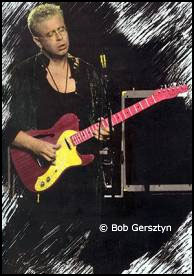

By Bob Gersztyn

News Index

November 2006 - In November 2006 Bob Gersztyn of FolkWax ezine published an interview he did with Bruce Cockburn. FolkWax has granted the CockburnProject permission to reprint that interview in full here. Enjoy!

Bruce Cockburn's musical history spans five decades and 29 albums. During the 1960s his bands, OLIVUS, The Children, and 3's A Crowd, shared the stage with everyone from Jimi Hendrix to Wilson Pickett in Cockburn's native Canada. After Neil Young bailed out of the Mariposa Folk Festival to join Crosby, Stills, & Nash at Woodstock back in August 1969, Cockburn took his place as the solo headliner. At that time he began a solo career, writing deeply personal and spiritual songs beginning with his self-titled album released in 1970. Ten albums later, in 1979, Dancing In The Dragon's Jaws provided an international radio hit when "Wondering Where The Lions Are" started to receive international airplay.

His newfound popularity expanded his horizons and, after traveling to Central America in the early 1980s, Cockburn's music began to take on a much more political tone. "If I Had A Rocket Launcher," from 1984's Lovers In A Dangerous Time" and "Call It Democracy" became anthems. His battle cry also included Native American rights, ecological issues, land mines, and, more recently, the war in Iraq.

Every Cockburn album holds a number of indelible compositions with hook-laden melodies that impale the psyche through idea-changing lyrics. A quarter of a century ago, 1981's Inner City Front produced the prophetic anthem "Justice," which excoriated mankind for inhumanities committed against itself in the name of everything including "Jesus, Buddha, Islam, man, liberation, civilization, race, and peace." 2006 has produced Life Short Call Now whose compositional subject matter includes the obvious war on terror, with titles like "This Is Bagdad," ecological issues represented by "Beautiful Creatures," and personal relationships with "Different When It Comes To You." The overall theme is reflective of his nomadic lifestyle coupled with the language of television infomercials.

Bruce Cockburn is echoing prophetic voices of the past like Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Malachi. He's a musical artist whose style combines the ancient and traditional elements of prophetic poetry with modern musical forms ranging from Folk to Rap. His music transcends the status quo. Although he's won every musical award Canada has to offer, he still has more of a cult following in the U.S. and around the world. After seeing Cockburn perform dozens of times over the past three decades and repeatedly listening to all 29 albums, it was with much excitement and anticipation that FolkWax senior contributing editor Bob Gersztyn sat down with Bruce to talk about his new album, among other things.

Bob Gersztyn for FolkWax: Are you touring with a band this time and if so are any of the musicians on the album?

Bruce Cockburn: Yep, they both are, Julie Wolf on keyboards and Gary Craig on drums. It's a trio format and they both are on the album. Julie toured with me before as part of a quartet on the last band tour that I did. Gary has played on a number of my albums, but has not toured with me before, so I'm actually very excited to have him on the road and we've had a really good week and a half just now, rehearsing a repertoire for the tour.

FW: Are you going to be doing any wailing electric guitar solos?

BC: Not exactly. In keeping with the generally acoustic vibe of this album we're sort of leaning that way more, but you never know what might come out. There will be a few moments.

FW: Why did you choose the title Life Short Call Now?

BC: It was the title of the song that was on the album, obviously, and it just seemed like a good title for the whole album. When I make an album I don't sit down and plan a concept. It's always when I have enough songs to fulfill the time requirements that we go into the studio to do an album. So whatever I've been encountering and writing about during the period of time leading up to that is what determines the content of an album. But after the fact we're in the studio recording the songs and we start listening to it all back and thinking that Life Short Call Now is a pretty good name for this album.

I guess that's for a couple of reasons, in addition to the sense that the song itself talks about being lonely and using the language of infomercials, "don't wait call now." Maybe it's a function of ongoing aging or maybe it's a function of the fact that we're a species that's destroying its habitat, but one way or another it seemed a little more urgent perhaps than they once might have seemed. It's like whatever you're going to do that's good in the world, do it now while you have the chance because it's gonna get harder as time goes on. So like I said, it's after the fact that I named the album with that in mind.

FW: That goes along with another song that you have on the album called "Beautiful Creatures." In it you say that the "...beautiful creatures are going away." Why are they going away and exactly who are they?

BC: Well, we're seeing the loss of thousands and thousands of species that we share the planet with. Like the ones that we're aware of, the ones with the romantic image that we can access as humans, that are kind of cuddly. There's a cuddly factor, if I can put it that way. Animals like polar bears and tigers, these animals are going to be gone. There's disagreement over what is behind climate change, but there's no question in my mind that whether there's a natural element to it. There's also a very strong element of human interference with the natural balance of things.

The arctic ice is melting, polar bears can't breathe anymore, their babies are drowning. They can't hunt for seals because seals don't have any ice to come up on. For the first time in the memory of the Intuit people, polar bears are starting to eat each other because they're not getting anything else to eat. It just seems to be heartbreaking that these beautiful creatures are leaving the way that they are. We're not really doing much about it. There's a lot of talk and, like I say, some of those particular species that are highly visible and highly symbolic for humans are noticed. People pay attention to that a little bit, but not enough to actually sort it out and way too late in the game, also, to sort it out.

There's all the other species, thousands of birds and insects and things that we don't normally think about or know the names of. Like creatures that live in the tropics and areas that are being clear-cut or otherwise messed with. We're facing the extinction of species that parallels the great extinctions of the past. In the past, those extinctions have been accompanied by pretty severe changes in the whole of the world's environment and we may not survive those changes if that's what we're faced with here, and it seems as though we might be, so life's short.

FW: How does war play into all of that?

BC: It's a complicated one. War is hands down one of the single biggest destroyers of environment that humans have come up with. It may be more localized than some of the other effects that we've had. In an area where fighting is taking place with modern weapons, the environment is going to be destroyed, period. I mean that's what happens. People, places, and animal habitats get burned, bombed; everything gets upset in that kind of setting. The thing is where the urge to fight seems to be an inescapable part of human nature, as much as the urge to love each other.

We have this schizoid thing going on where, on the one hand we're capable of envisioning the great glories of a loving world and the benefits of being respectful and kind towards each other, and yet we don't seem to be able to stop killing each other at the same time. That's why I say it seems to be an inescapable part of our nature. I've said this before, kind of with respect to the last album, not Speechless, but You've Never Seen Everything. It seems to me that when I wrote the songs on that album that we were in a race between the discovery of the true, for whatever better way to put it, cosmic connections that exists among us all and between us and the environment that we live in, the planetary system that we live in, etc. There is a race between the recognition of those things and the innate urge to self-destruct, and there's a lot of human behavior, a lot of the big strokes and big decisions are being made by people who are acting in service of that self-destructive urge.

FW: Did you actually meet the mercenary that you sing about in "See You Tomorrow"?

BC: Yeah. I got offered a job when I was going to the Berklee, B-E-R-K-L-E-E in Boston, not the famous California place. I was going there in the mid-1960s and I got offered this summer job with this guy who was going down to Central America to run guns to Cuba.

FW: How did you get an offer like that?

BC: I just knew somebody who knew somebody. One of my dorm-mates had this ex-military friend who was going to do this and he wanted somebody to go watch his back. At first I thought it was kind of a cool idea and then I realized what he wanted was for me go down there and get between him and people that wanted to kill him and I thought, "Hmm, maybe not." So at that time and that age, I was 18 or 19, and the moral implications were not evident to me. Now they would be, of course, anytime something like that comes up, but back then I really didn't think about that. It was just like this could be cool, never did anything like that before. But thank God I decided not to do it.

FW: Yeah, definitely, that would be a pretty dangerous sort of thing.

BC: You think? And not even a good thing. Whatever Castro's faults are, the returning of Cuba to its previous sort of rule was not a good idea and that's what they were trying to do, of course, to roll back the Cuban revolution.

Part Two

Bob Gersztyn for FolkWax: I once read or heard that you played on the same stage with Jimi Hendrix in The [Greenwich] Village. I think that you were in a band?

Bruce Cockburn: Not in The Village. We opened for Hendrix in Montreal actually, in an arena.

FW: Was that with The Children?

BC: No. At that time the band was called Olivus, which is spelled O-L-I-V-U-S, which of course was supposed to sound like "All Of Us," and we thought that it was terribly clever. It's kind of embarrassing to think about it now, but anyway, that was the name of the band and we had a few really cool opening gigs. We opened for Cream in Ottawa and we opened for Wilson Pickett in Toronto and we opened for the Lovin' Spoonful somewhere. That one was The Children. There were some interesting gigs that we had, but they were few and far between. Mostly we rehearsed and didn't have gigs. There was a review in one of the Montreal papers, which somebody showed me in Paris actually, a couple of years ago. I was there doing PR for an album, whatever album had just come out, and the guy from the record company that was driving me around was a big Hendrix fan. I said, you know, I opened a show for him once. He got all excited and his friend who has a Hendrix website came up with a reprint of this review from the Montreal Gazette, I think. There used to be a couple of English papers back then in Montreal, which said that if it had been anybody but Hendrix we would have been the stars of the show. The guy really liked us, which leads me to suspect that he was heavily influenced by LSD at the time.

FW: [Laughter]

BC: I don't think we were very good, but in any case there is a record of that having happened.

FW: Speaking of LSD, I have a question that I wanted to ask you. The line in "Mystery" that goes "I stood before the shaman, saw star-strewn space, behind the eyeholes in his face" sounds to me kind of like a peyote vision. How do you feel about the usage of substances like that for creative purposes?

BC: I think that it's perfectly fine, if it's directed and conscious. A lot of people take those kinds of things just to get stoned. I did my share of LSD back in the day, but not on the occasion that the song refers to. I was totally straight, in the middle of an afternoon. The shaman in question was the guy who painted the painting that we used on the cover of Dancing In the Dragons Jaws. He was the first native painter to come out and actually paint their myths. He became very famous for doing that. He's from the western part of Ontario originally. He may have died, I'm not sure, because he sort of faded into obscurity, but for a while he was really influential and famous as a painter. He influenced a whole generation of other native artists to similarly paint their own myths and spirituality in their own imagery, not in kind of white people's or European imagery. He got a lot of criticism from other native people for that, but he was a shaman. At least he said he was.

We went to his apartment; well, at least to an apartment that he was temporarily staying in, in Toronto. At one point during the conversation with him I had this vivid...I was looking at his face and we were talking about tea or something totally inconsequential, and I'm looking in his face and I had that experience of where his eyes were windows into space and it freaked me right out and I didn't say anything, but he saw me react or something. He saw a look come over my face I guess, and he kind of smiled and didn't say anything. He kind of smiled a knowing smile and that was the extent of it, but it was shocking. I had to assume it was something real because I wasn't stoned. At that point it had been a long time since I did anything like that. I gave up on all that kind of stuff really at the end of the sixties, even before that. So it had been at least ten years since I'd done any of that kind of stuff and there he was. I don't make any of this shit up. People think it's imagination, but it's not. I don't have any imagination, I just report.

"I don't have any imagination, I just report."

FW: I was talking to Peter Bergman from the Firesign Theater and John Sinclair, the manager of the MC5, a couple of years ago and I asked them what benefits the 21st century was reaping from the 1960's counterculture, and they told me that other than helping to stop the Vietnam War, changing music, and allowing liberality in clothing, nothing. What do you think?

BC: I think that there is, but it's hard to access. One of the things that happened in the 1960s was Vatican II, in which Pope John XXIII convened all the bigwigs of the Catholic church to decide what the destiny of the church should be and what role it should play in the modern world. It was decided at that time that the church would be the church of the poor. It was decided that I think because the vibe of the sixties, the kind of philosophy and energy that was flowing around. It flowed through the clerics as much as it flowed through everybody else. I mean it was just in the air. It touched everybody, whether they wore the uniform or not...of the hippie movement I mean. As a result of Vatican II the church began to teach people in Latin America to read. As a result of people in Latin America learning to read they started trying to overthrow the governments that were keeping them poor and malnourished and not getting medical attention and all sorts of stuff. Many church people became supporters of that kind of social change, and we've been living with the result ever since.

There is just one case where the sixties definitely affected current history and is still affecting it, because those revolutions have come and gone and they've been repressed violently in almost every case, but the reason for them being there hasn't gone away so they keep coming back. It was the church deciding to identify itself with the poor that changed that, and I really think that wouldn't have happened in any era other than the sixties, in the same way that it did. We don't still have a Vietnam War because people in the sixties decided that they'd had enough.

I also think that the Civil Rights movement became successful because it had the support of, not just because of this of course, but one of the things that contributed to the success of the Civil Rights movement was the support of White liberals who constituted a voting bloc that politicians had to pay attention to. It wasn't just a sudden humanitarian awakening on the part of the government of the day. Their awakening had to do with pressure from voters and the anticipation of losing elections and stuff like that. That's a little before the hippie movement, but it was still going on, still evolving as it is today, because the need is still there for it to evolve and things are not quite equitable yet. I just see all these trends that are going on. The fashion comes back and the young kids going around looking like hippies today don't have any idea what it meant to be looking like that in 1967. Because people used to hassle you for looking like that back then and now they just think that you're weird.

FW: Five or six years ago I was at a Hot Tuna concert and many of the people were dressed in hippie garb. I mentioned something about the counterculture to a young woman standing next to me and she took offence. "I'm not part of the counterculture," she said, as her boyfriend gave me a dirty look. I thought that it was funny.

BC: Well they're not because they got it out of fashion magazines. It's more than a thing, because the Rainbow Family still exists, right? The Grateful Dead, throughout their life span as an entity, attracted these huge crowds of people of all ages that wanted to carry on that sensibility and a lot of this was for fun, but it was a thing that you identified with for fun. I knew high school kids in the nineties that were Grateful Dead fans, who would go everywhere to their shows and those kids are now adults. They've grown up with that sensibility and identified themselves with it. So I don't see it disappearing and I don't see it being meaningless. The thing you have to remember too is that being a hippie in the sixties was also a fashion statement.

The first time I ever heard the word "hippie" was in 1964, when I went to Europe the first time. Before that people would call us "beatniks" or "hipsters," or whatever. I remember meeting this guy with hair down to his butt and a big, full beard. He was an English guy, but he was hitchhiking back to England after having participated in the blowing up of a statue of Franco in Spain, according to his story anyway. I said something about beatniks and he said, "we're not beatniks, we're hippies." That's the first time I'd heard the word hippie, and I thought it had obviously evolved from hipster and whatever. It was like, okay, well that's a word. But at that point the people that would identify themselves that way were a very conspicuous minority. Bell bottoms weren't fashionable and the hair styles weren't fashionable, they were counterculture, but within a couple of years of that everybody that was coming out of high school had long hair and had bell bottoms. The fact that they identified with a set of values that was not their parents' set of values doesn't make it less of a fashion event. So it never really was a lot more than that. There was more going on. You didn't have to be a hippie to oppose the Vietnam War; it just happened that most of the people who opposed the war were of that generation who came out of high school wearing bell-bottoms and long hair. I think, anyway.

FW: Thanks for taking the time to talk to us.

Bob Gersztyn is a senior contributing editor at FolkWax. You may contact Bob at folkwax@visnat.com.

Folkwax is an electronic publication from Visionation.

You can access this interview at FolkWax

~bobbi wisby

News Index

This page is part of The Cockburn Project, a unique website that exists to document the work of Canadian singer-songwriter and musician Bruce Cockburn. The Project archives self-commentary by Cockburn on his songs and music, and supplements this core part of the website with news, tour dates, and other current information.